RAW IS WRONG IN 2024 – Film Advice

02 Sep 2024, Posted by in Reviews, Uncategorized

It’s time to talk frankly about RAW.

Some cinematographers insist that shooting Raw is always the best choice, but the argument for Raw’s superiority is outdated, and its disadvantages outnumber its advantages. Despite Colorist’s love of Raw, and despite Arri and Red and Apple and Atomos dearly wanting you to believe in the supremacy of Raw, the evidence points in the other direction. I’m sure this argument will rile some feathers, but please read on….

Before we jump in, let me say that we’re not comparing RAW versus 8 bit, or 4:2:0 footage. That’s ridiculous. If you’re shooting RAW, or considering it, you’re probably already working with 10bit and 4:2:2 files. Or you’re debating a RAW vs 10bit workflow change.

Raw came into being in 2003 at a time when digital video was exploding with technical advances. RED developed the first RAW camera in 2006. It’s important to remember that at the time everyone was filming in HD; 4K capture wasn’t developed until 2007. 4:2:2 subsampling was the digital norm in Hollywood, with feature films like Star Wars II Attack of the Clones being filmed with the Sony HDWF900. RAW video was developed for professional filmmakers and the quality was next level. But in the 21 years that followed, resolution has increased, new codecs have been introduced, compression techniques have improved, and the distance between Raw quality and Processed video has gotten less and less. So much so that, Arri will say that Apple ProRes 4:4:4 is, and I quote, “almost indistinguishable from uncompressed (RAW) UHD material.” And Apple will say that ProRes 4:4:4 is virtually indistinguishable from HQ 4:2:2. Does this mean that Arri Raw is visually indistinguishable from ProRes HQ 4:2:2 video? Well… basically, yes. Arri and Apple just said so.

WHEN YOU CAN’T SEE THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN RAW AND PRORES HQ

But why? 12-bit Raw files have four times as much information as 10-bit. Why isn’t there more to see? The answer, no one will be surprised to hear, is a bit complicated… but resolution, bit depth, and LOG all play a role.

Raw is all about color— and by “all” I mean only. Raw does not capture more physical detail; that is a function of resolution (HD vs 4K vs 8K). Nor does it capture more dynamic range; a camera that has a dynamic range of 10 stops in a processed image will have 10 stops in the Raw image. It’s the use of a LOG format that increases the dynamic range to 12 stops (as an example). Raw doesn’t produce smoother highlights or blacker-blacks, either. With Raw, it’s the amount of color information that increases— specifically to 12 or 16 bit, and 4:4:4. Why isn’t 12 bit nicer to look at? Because our eyes can’t see that level of chroma variation, and our screen is most likely 8 bit.

As we all know, the screens we view content on are 8-bit; 10 bit produces far more color variance than our screens need, providing welcome leeway when it comes to manipulating the image in post. The question is, “when are the extra colors more than we can use?” There’s a point when the images, even under extreme grading conditions, will be identical regardless of how many more bits we throw at it. How much is more than enough? 8-bit footage has 256 shades of red that cover the full range of the red spectrum. If we think of these shades as spread out over 100% of the spectrum, each “shade” is roughly .4% (or a half percent) apart on the spectrum. This isn’t exactly correct due to gamma curves, etc., but it’s the best way I know to explain it without math. The human eye isn’t able to see chroma differences that are smaller than 1%, so the image appears smooth… without bands. If we add a lot of contrast, the difference between each color becomes greater than 1%, and the color change becomes noticeably abrupt. A 10-bit sensor has over a thousand colors of red across the range, each less than 0.1% (or 1/10th of a percent) from each other. In those terms it’s easy to see why it’s much harder to “break” a 10-bit image into bands. Twelve bits, with over 4,000 data points for each color, is essentially “an extra extra” according to Arri and Apple. It’s not distinguishable… or visible to the human eye.

It’s a common misconception that 4:2:2 leaves out color information… or simply duplicates it to the next pixel. This is inaccurate. The chroma information is copied between alternating pixels, but the luminosity of each pixel is recorded in each, which means the color/chroma being copied will look different (the same hue of red will look different if the luminosity has changed). There’s not less color information, it’s just less accurate. The first pixel is recorded with perfect color fidelity; the second, copied pixel may (or may not) be recorded with perfect fidelity; the third pixel will be recorded with perfect color fidelity; and so forth. If our eyes could discern individual pixels, we might notice differences between 444 and 422 images in places where the color changes significantly; and Raw advocates will say that software can see the difference. But this is only true when comparing footage with the same resolution– Raw HD vs 422 HD. When we acquire the footage in 4K and down-sample to HD for output we increase our subsample from 422 to… well, no one seems to have an accurate number here, but it’s generally agreed that it’s more. Subsampling increases whether down-sampling is done in camera (such as with Sony a7III 4K footage) or in post. When Raw was invented, we had LOG but not 4K resolution, so software could see a difference. If you down sample (and who isn’t capturing in 4K now?), you may be acquiring footage as 422, but your chromakey software is seeing footage closer to 444.

When filming in LOG, all of the data is acquired, regardless of whether you’re filming in HD, 4K, or 8K. Charles Poynton is one of the leading experts in the field of color. He (and others) will tell you that cameras can fit 99% of 12-bit Raw file data into a 10-bit LOG file. The problem with gamma profiles is that there’s a limit in how much color information they can include in each stop of exposure. 10 bit 4:2:2 capture can produce more data than a gamma profile can encode when that data is spread unevenly (for example, a snow scene with an excess of data in the highlights). Logarithmic profiles, on the other hand, both reduce the dynamic range of the image and “allocate storage” to where it’s most needed. This means that color data is never lost in 10 bit 422 LOG files; we have everything to work with. I point this out because with 10bit footage there’s lots of color information we don’t see… which means a gamma profile may be discarding some of that invisible info. The image looks great out of the camera, but if we adjust it in post it may fall apart more quickly.

And Then There’s Real Life

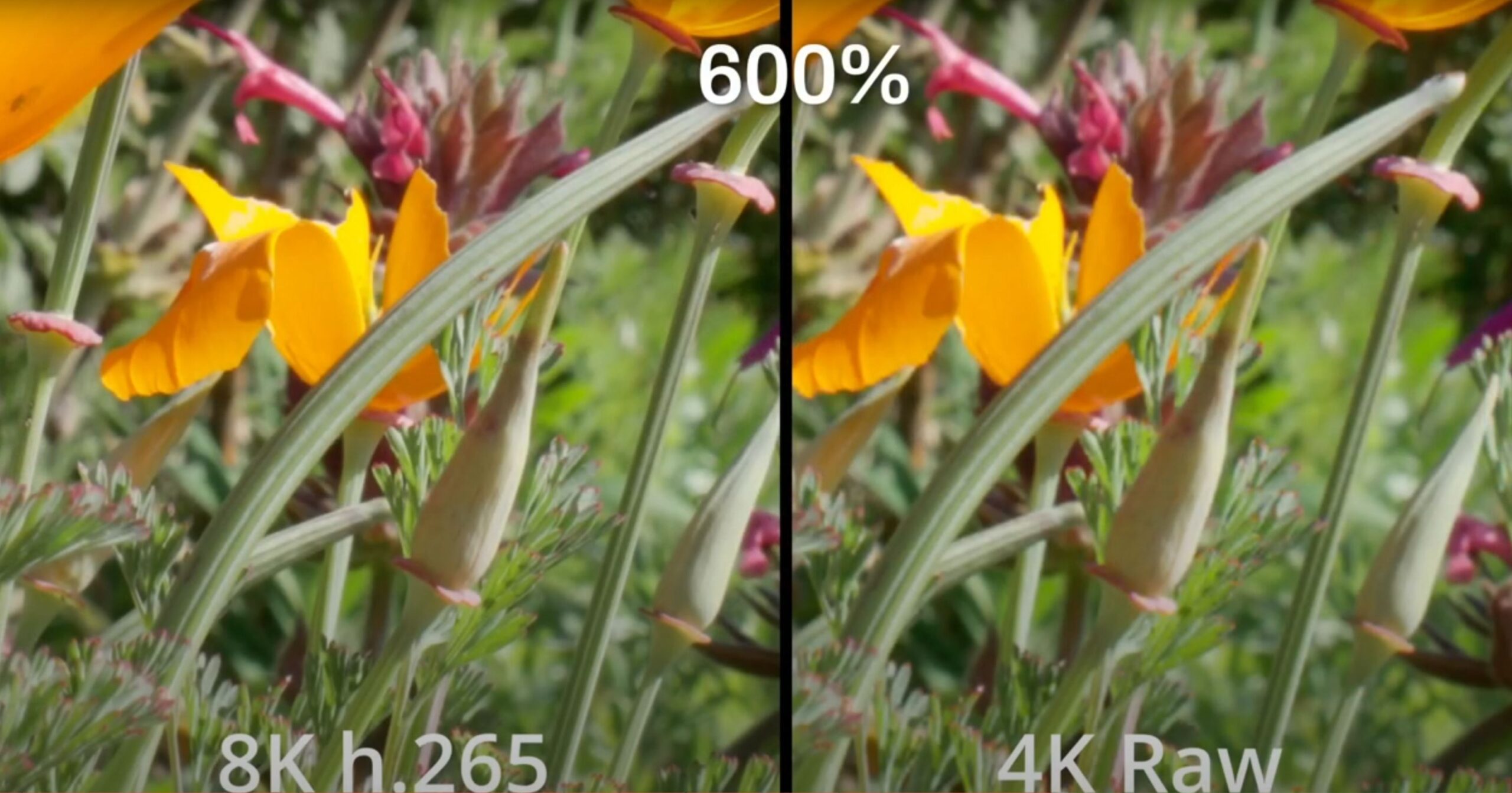

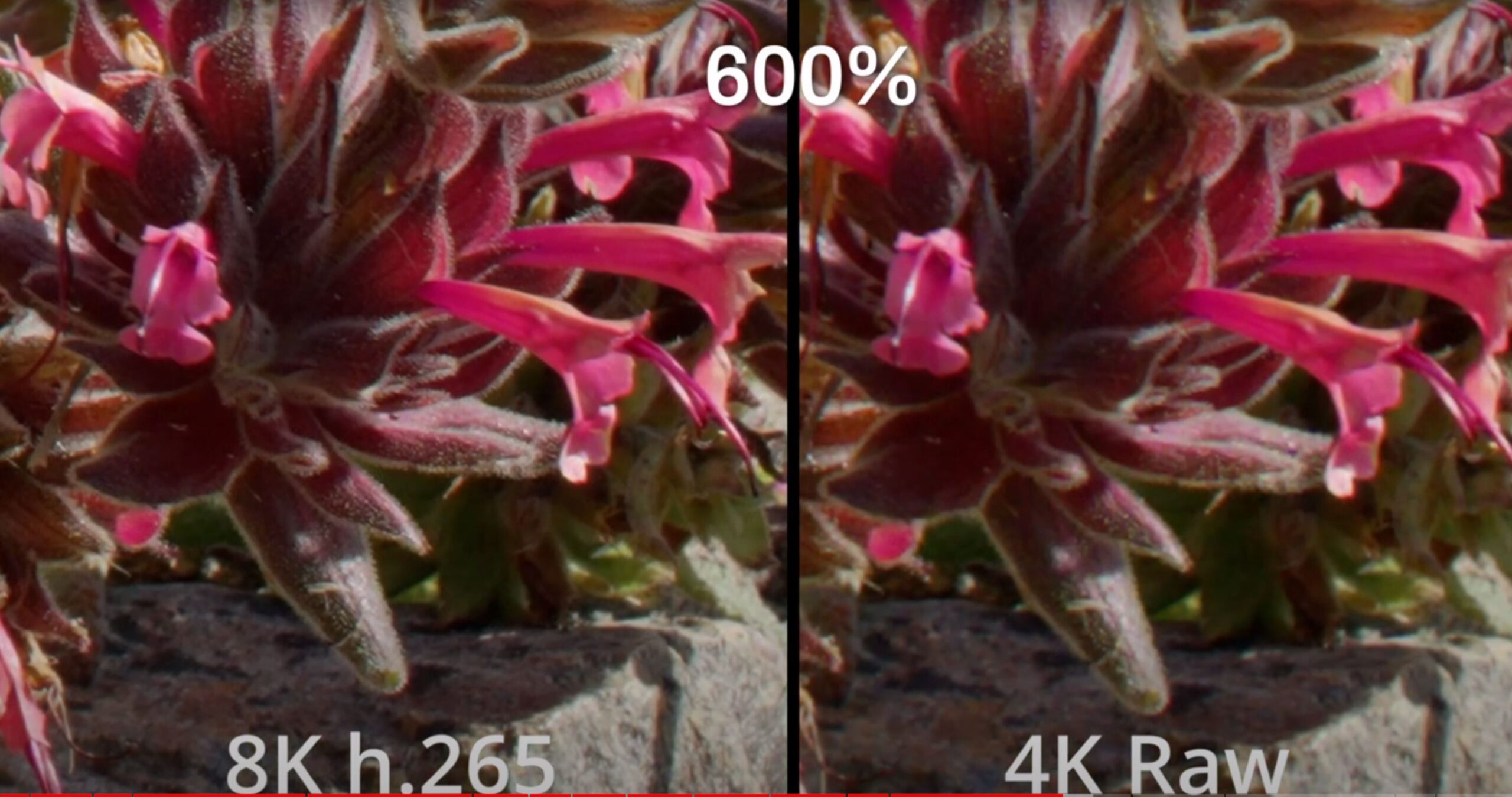

Numbers and theories are great, but do they hold up in real life? Our two statements from Arri and Apple are examining different links in the image acquisition process. They may not add up to the conclusion that Raw files will never show their extra data. Perhaps we see the difference between Raw and processed images in real world footage? I compared the 4K Raw footage from my Sony a1 to its 8K output (I chose 4K and 8K because it’s the highest quality in both Raw and 422). Here’s what the images look like:

For my first test, I chose a scene with a fairly normal set of challenges in terms of dynamic range and color. The Raw and 8K images have the exact same grade, and then zoomed in to 600 percent in order to really pixel peep the differences. It’s been outputted in 1080p. As to be expected, there’s slightly more detail in the 8K footage. The colors, however, appear identical. Those extra bits are, indeed, invisible.

The next image is the same: more detail in 8K, same color information.

There was only one test shot that appeared to show any difference beyond sharpness. Here the shadow side of the tree appears to have more color depth. In all honesty, I can’t say if this is the result of more color data, or simply a difference in the way the H.265 codec captured the image.

Is there more saturation in the dark areas or is it just different exposure curve? Here is the full image for reference:

As you can see, this image is considerably more challenging, with a range from dark shadows that need some level of detail to blue sky and clouds.

The Disadvantages Add Up

Advocates of Raw will point out that it offers you ability to change ISO and color temperature in post, and to be more selective with noise reduction and sharpening. This is generally true— though not all Raw formats have the ability to adjust color temperature. Editors and colorists will surely appreciate those features when they’re needed; but cinematographers, DPs, and camera ops are doing their job as well, picking the best camera, ISO, color temp, and settings in the moment. These benefits of Raw are only useful when other professionals make mistakes (and sure, that does happen). But the disadvantages of Raw are ever-present. Raw produces huge files that often need to be converted and always need to be stored. As of this writing, cameras can’t provide lens correction in RAW, or active stabilization, or high frame rates.

Colorists may argue that Raw footage is more durable when applying extreme grades; I’d argue that in those rare situations where extreme grading is required, Raw often is not reliably more durable . RAW footage, under certain grades, becomes more noisy and more artifact filled.

I performed an extreme grade on 4K footage in both H.265 and RAW. Both were shot in SLOG 3, exposed the same, color graded the same, and then had the saturation increased to 200%. (The RAW footage was converted to ProRes 444 XQ for use in Davinci Resolve). These images were zoomed 200% for pixel-peeping purposes, and exported in 1080p.

Original size noise test, graded

As you can see below, both images are tortured by saturation, but RAW version has both more color noise and more noticeable color fringing— something that’s nearly impossible to correct in post. What’s more, neither image started to band, even with an absurd amount of saturation.

Extreme grading of 4K 422 SLOG 3 cropped closeup

Noise in 4K RAW footage cropped closeup

In this scene, the Raw footage performed noticeably worse when the grade was pushed. I’m sure other colorists and editors can provide examples where it performs better, but the idea of reliability is extremely important. If you don’t know whether or not the Raw image will be better, then you have a problem.

Being a cinematographer who swore off RAW early, I don’t have the broadest experience in grading Raw footage (and probably not the most expertise in shooting it, either); my conversion process may have added some instability to the footage. I also think it’s fair to ask why professional colorists don’t complain about these problems with Raw. The answer may be that a professional wouldn’t increase the saturation by 200% across the entire image; their extreme scenarios aren’t that extreme. The tools to repair, mask, and adjust make it possible to grade Raw footage within its boundaries. And let’s face it, chromakey technology has improved immensely since the first Raw camera was introduced in 2006.

So, Raw versus 10bit 422… is Raw better? I know this is going to cause a minor uproar, but I think the answer is no. In the real world where reliability, file size, lens stabilization matter, higher framerates matter, and the actual benefits of more color data is illusive, 10bit 422 footage is better. What would I recommend for the best footage? Shoot in the highest combination of resolution (4 or 8K), bit rate (10bits), and bit depth (4:2:2) available to you. Use a higher resolution than your final output if possible. And when considering Raw, test shoot it with your actual shoot conditions.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.